Mini-Grants: Cloud Forest Regeneration Project

Support our Mini-Grant Program

Quaker Earthcare Witness offers grants each year to diverse Friends meetings, groups, churches, and organizations to support their community’s vision of caring for the Earth and each other through our Mini-Grants Program. Please help us continue this work. Right now, the first $4,000 in donations will be matched! Double your impact by giving today.

Cloud Forest Regeneration Project

By Paula Kline & Alan Wright, Westtown Monthly Meeting

The cloud forest is a magical place to visit. It is both the most diverse and the most endangered forest ecosystem in the world. As of this year, only an estimated 1 percent of global woodlands were cloud forests, compared with 11 percent in the 1970s.

While only .8% of the land area in Mexico is cloud forest, there are 2,500 plus plants that prefer or are exclusive to this ecosystem. It is an essential habitat for many of the migratory birds we enjoy in the United States. Due to land cover changes, illegal logging, and cattle grazing, the cloud forest is an endangered ecosystem.

The small city of Huatusco in the state of Veracruz was once nearly entirely cloud forest habitat. From 2001 to 2021, Huatusco lost 1,700 acres of tree cover. The impact of this loss of tree cover on the community is dramatic. The area has seen both flooding and significant drops in water levels. Local villages are scrambling to maintain access to predictable water supplies. This creates health and sanitation risks for everyone. This is more than just an inconvenience for Mexican households. The conservation and restoration of cloud forests are extremely important to support biodiversity and ensure the provision of ecosystem services – especially water quality, water availability, and flood mitigation.

Deforestation, combined with increasingly unpredictable weather (including unheard-of droughts, hailstorms, and freezes), is threatening the other inhabitants of the ecosystem. A 2022 study of the Mexican cloud forest reported that if unprotected cloud forests are cleared, 99% of the entire ecosystem could be lost, resulting in the extinction of about 70% of endemic cloud forest vertebrate species.

Scholar and activist Joanna Macy observes that in restoring our relationship with nature we must both stop doing harm and shift our awareness in our relationship with nature. This dramatic loss of cloud forest did not happen on its own. It was lost due to a lack of understanding of our interdependence with the cloud forest ecosystem.

So, how did two Concord Quarter (Philadelphia Yearly Meeting) Quaker educators end up doing reforestation work in the cloud forest of Mexico? We first heard about the amazing work being done by a young couple, Ricardo and Tania Romero. Meeting the Romeros at their project, called Las Canadas, in 2003 was life changing. While their 600-acre cattle ranch had no electricity or running water, they discovered they possessed a rare fragment of intact cloud forest. It led them to sell their cattle and replace them with a small dairy herd to stop any further ecological damage. These innovators radically changed their lifestyles to reflect what they understood about climate change and threats to biodiversity. Through workshops and apprenticeship programs, they invited others into the process of sustainable agro-ecology. They committed most of their lands to a first-of-its-kind land conservancy in Mexico.

We saw in them the spirit of the Quaker impulse to align with the truth – they acted on what they understood about our broken relationship with the natural world. It prompted us to consider what it would look like if we took that relationship just as seriously. What actions were we willing to take to prevent further harm and begin to heal our relationship to the cloud forest in particular? We knew healing actions were required on multiple levels. We landed on two strategic pathways: (1) conservation/restoration (preventing further harm and repairing harm done) and (2) nurturing and promoting spiritual and ecological literacy to shift individual, household, and community practices in relation to the cloud forest ecosystem.

Preventing further harm and repairing the damage

In 2003, we brought the first of many groups of high school and college students to experience a Quaker environmental leadership work camp in collaboration with the Romeros. It was in this context that we experienced a great opening to be of service to this habitat. Ricardo informed us that his neighbor wanted to sell 100 hectares (or 250 acres) of degraded land with only a fraction of cloud forest remaining. We felt strongly led to take this next step, not really knowing what we were getting into. We named the project Las Bellotas or the “Acorns” after both the endangered oaks found on the property and the symbolism of new life from acorns.

Our first step was to get guidance since neither of us is a trained ecologist. We turned to the National Institute of Ecology in nearby Jalapa. Their faculty gave us a framework for this work. They introduced us to restoration ecology, a process of assisting in the recuperation of an ecosystem that has been degraded, damaged, or destroyed through both active and passive approaches.

Restoration ecology requires a reference for the ecosystem. What does a healthy cloud forest look like? We were so fortunate to have a number of legacy tree species that had not been logged. In addition, we had a small but healthy ecosystem in our neighbor, Las Canadas, whose restoration work was at least 10 years ahead of us.

Because we had so much land degraded by decades of grazing, we started with active restoration. This approach takes more time and is more costly than passive restoration, but this land needed a jump start! Our first steps were to collect seeds from the remaining mature trees and start a nursery. We also received help from a Mexican foundation and purchased native tree species. In the first year of active restoration (2005), we planted 27 tree varieties and 10,000 trees. In 2006, we focused on 17 varieties and planted 10,809 trees. In 2007-9, we planted 30 varieties (including shrub layer plants as well) and a total of 17,804 saplings. We continued to plant at a slower rate over the next 10 years.

Needless to say, not all of the 40,000 saplings survived. Our most common challenges were ants, mice, and other larger rodents, unexpected killing frosts, and the encroachment of exotic grasses that had been planted for cattle. For some trees and in some years, we faced high mortality rates.

Once the active phase was underway, we also selected areas for passive regeneration. In these areas, we let nature take its course. In some of these areas, the bracken took over, but in others, we saw dramatic resilience.

Last year, we celebrated the 20th anniversary of our relationship with this patch of cloud forest. You can see the contrast between the aerial photo from 2003 and the more recent one. Our biologist colleagues who measure our progress have seen an increase in birds, reptiles, amphibians, and most recently, mammals, including the jaguarundi and foxes. We have met our first goal to stop doing harm on this parcel of land.

Photo: Left is a photo from 2003 prior to the reforestation. Right shows progress made.

In the last few years, we have also begun healing our relationship with nature by assisting in the recuperation of the ecosystem as a whole. We now play a pivotal role in a regional cloud forest regeneration project. With the help of QEW, we have committed to producing 10,000 saplings a year to be planted in the region through schools, municipalities, and private landowners.

Healing our own relationship with the natural world

The second strategic pathway supports the awareness of our relationship with one another and the natural world, putting the healing of that relationship at the very center of things. In 2017, a spacious, beautiful, ecologically constructed meeting facility was inaugurated for the Center for Spiritual Ecology. Programs at the Center make visible the positive options for healing our relationship with nature by giving individuals direct experience with the cloud forest and hands-on exposure to the tangible benefits of sustainable building, eating, water use, and renewable energy practices. They offer day programs, welcome volunteers, and offer multi-day programs for small groups.

The Center serves educators and students from pre-K to university. Carlos Rojas’ rural high school is a case in point. For many years, Carlos brought his students to the Center to experience firsthand the value of protecting the cloud forest. His students collected and planted the acorns for the endangered oak known as the chicalaba. During one visit, the Center learned that the irregular availability of water was forcing the school to close. Imagine being sent home from school because, with no water, there is no toilet flushing. No water, no hand washing. No water, no food prep.

Working with Carlos’ students, the Center sponsored a workshop on composting toilets. With the Center’s support, students and parents worked with a mason to install composting toilets and rainwater cisterns which allow the school to keep its doors open. Principals from other rural schools have come to visit Carlos’ school to learn what they can do. As importantly, the work with the Center shifted how the students, parents, and faculty looked at their relationship with the Commonwealth of Life. They began to speak of their relationship with the cloud forest and their cloud forest’s relationship to the rivers and streams. They found language to speak of the harm they now recognized had been done to the ecosystem and what their role might be in its restoration. And they began a tree-planting campaign close to the school itself.

Looking forward: What You Can Do

In May of 2023, we were awarded the designation of an ecological reserve by the state of Veracruz. We know this is a very small step toward the international goals set by the 2022 UN Biodiversity Conference, (COP15), to reverse the unprecedented destruction of nature. One of the targets, known as 30 X 30, aims to protect 30 percent of the planet’s land and water by 2030. Just as we were inspired by the Romeros, we hope other Friends will be led to follow our example on their own properties or to support us as we expand our restoration work throughout our watershed in Mexico.

Felix Colorado (left) coordinates the expanded nursery, thanks to QEW Mini-Grant support,

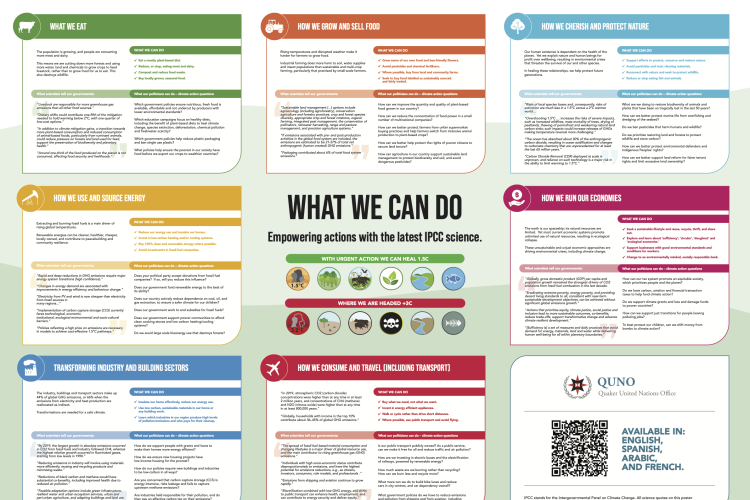

Below are some resources for you to consider on how you can protect local biodiversity.

If you want to learn more about our project, you can watch this Greening Sacred Spaces workshop.

If you would like to contribute to our project, please visit our GoFund Me site. If you are interested in visiting the project, please get in touch!

Resources to learn more about your own options for land stewardship, please watch the other Concord Quarter webinars

Greening Sacred Spaces: NWF Certification and Homegrown National Parks

Greening Sacred Spaces: Audubon Bird Friendly Yards