Community Choice Aggregation: Pennsylvania Boroughs are Ready for 100%

Join a webinar sponsored by Philadelphia Yearly Meeting’s Environmental Justice Collaborative on Community Choice Aggregation on January 18th, 7pm Eastern.

Presenters from the CCA for PA team will provide an overview of CCA, introduce participants to local leaders from the five boroughs that have already signed an MOU, and explain how this will work in PA to help boroughs meet their commitments to acquire 100% renewable power.

If you live in or near a borough, please consider attending. You can make a real difference in bringing more clean energy to Pennsylvania. Community Solar is not yet legal in PA, but CCA is and it just might be better!

by John McKinstry

One of the most exciting opportunities to take action on behalf of our Earth and slow climate change in Pennsylvania is through implementing community choice aggregation (CCA).

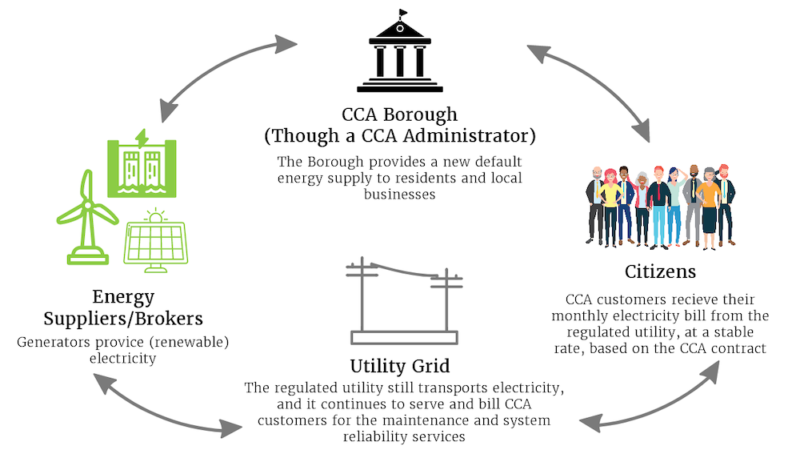

CCA enables an entire community to convert to green electricity rather than doing it one household at a time. Ten states currently have CCA programs: New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New York, New Jersey, Maryland, Virginia, Ohio, Illinois, and California.

In Pennsylvania, the authority to implement CCA is available only to boroughs (not townships or cities.) Even so, CCA is an essential way for local governments to help us transition to non-carbon energy sources, especially considering that there are over 900 boroughs in the Commonwealth! Five Pennsylvania boroughs have already taken steps toward implementing a CCA program (Narberth, Swarthmore, Media, Lansdowne, and Hatboro), and many more have expressed interest in doing so.

There are several advantages of establishing a CCA in one’s borough.

First and most obviously, it can significantly change the electricity market. In New York State, for example, municipalities had 5-10% of their residents using green energy before CCA. The number was low because people had to opt into a green electric generator where the default electric supplier burned fossil fuels. After CCA, where the model switched so that the default electric supply was renewable energy and an individual had to opt out of the green source, CCA communities had 80-90% of their residents using green energy.

Secondly, CCA offers consumers ease and protection. With the municipalities’ CCA Administrator monitoring the electricity provider, the terms of the generator contract will be fair and adhered to. CCA results in a community obtaining green electricity at competitive rates by virtue of the group buying power. Moreover, the terms will be fair to the consumer. Gone will be the days when one signs up for a generator, not seeing the fine print that allows the utility to triple the cost of electricity when no one is looking.

Third, CCA promises stability since renewable energy sources will be fixed by contract.

Fourth, CCA can change the market from the supply and the demand side. With local electricity control, a borough can encourage and provide a market for local green energy projects and jobs. A borough might arrange to install a neighborhood solar array over a parking lot, providing more EV charging and selling the excess electricity to the local residents and small businesses.

So what does this have to do with Quakers? Just as Pennsylvania gives this enormous CCA power to local control, so too do Quakers work well at the local level. Members of a meeting or the entire meeting can talk directly to the local envi- ronmental advisory council, sus- tainability commission, or borough council about establishing a CCA. It can network with other churches concerned about climate change and make a persuasive case for the planet and the consumer. A meeting can also network with other Quakers in boroughs through the Commonwealth on their progress and share resources.

John McKinstry is the co-chair of Swarthmore Borough’s Environmental Advisory Council. He has been a teacher and school administrator before retiring in 2020. Before teaching, John was an environmental attorney, working for the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection’s Office of Chief Council.