The Legacy of Quaker Boarding Schools for Native Americans: On the Debts We Owe the Past and the Ghosts of Our Becoming

by Allen McGrew.

Convinced Friends may wonder why they should accept responsibility for the abuses of Quaker boarding schools that received native Americans over a century ago. If so, they might also ask whether they can claim the heritage of John Woolman, George Fox, Margaret Fell or other historical Friends. We might also ask whether the descendants of those harmed have the luxury of denying the still-living legacy of the injustices done to their ancestors?

For my part, I cannot indulge the luxury of picking or choosing which aspects of Quaker heritage I choose to claim or disclaim. My mother’s great grandfather, Joel Johnson, was a supporter and sometimes Trustee of one such Quaker boarding school, White’s Institute in Indiana. In 1870, Indiana Yearly Meeting named him to the visiting committee for the institution.

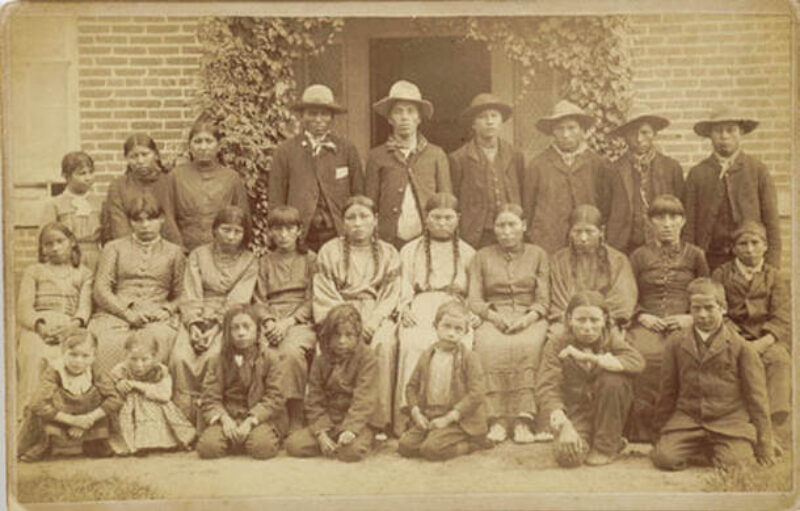

White’s Indiana Manual Labor Institute was the founded with a bequest to Indiana Yearly Meeting by Josiah White, a nineteenth century Pennsylvania Quaker, industrialist, and philanthropist. White’s vision for the institute was to provide an education for poor “boys and girls without distinction of color, White, Indian, or Negro” (Green, 1929). In 1882 the Trustees contracted with the government to provide education for Native American children for annual payment to cover boarding costs. This arrangement continued until 1895. At its peak, eighty-seven Native American children from thirteen different tribes were in attendance.

One of those children was a Lakota girl from the Yankton Reservation, Zitkála-Šá (“Red Bird,” also known by her missionary and married name, Gertrude Simmons Bonnin). She became a leading voice for Native American people and a visionary defender of their distinctive identities. She gained acclaim for writing the libretto and songs for the first Native American opera, The Sundance Opera (1913) based on sacred Sioux rituals, which her people had been banned from performing on their reservations. Subsequently, in 1926, she founded the National Council of American Indians to lobby for the rights of full U.S. citizenship to be extended to native peoples.

The discovery of Zitkála-Šá‘s poignant writings brought home for me personally the acute trauma inflicted on the native children at White’s – trauma in which my own family and community had been complicit.. “Our mothers had taught us that only unskilled warriors who were captured had their hair shingled by the enemy,” she writes. Rebelling against such an indignity, she flees and hides but cannot escape the inevitable pursuit of her custodians at the boarding school:

“What caused them to stoop and look under the bed I do not know. I remember being dragged out, though I resisted by kicking and scratching wildly. In spite of myself, I was carried downstairs and tied fast in a chair. I cried aloud, shaking my head all the while until I felt the cold blades of the scissors against my neck, and heard them gnaw off one of my thick braids. Then I lost my spirit. Since the day I was taken from my mother I had suffered extreme indignities. People had stared at me. I had been tossed about in the air like a wooden puppet. And now my long hair was shingled like a coward’s! In my anguish I moaned for my mother, but no one came to comfort me. Not a soul reasoned quietly with me, as my own mother used to do; for now I was only one of many little animals driven by a herder.”

And now I must ask, what am I to do with such knowledge? What am I to do with the awareness of my own family’s complicity in this harm? Am I to renounce my ancestors? Could I? Would that not seem like cheap distancing or hollow chest-thumping? On the other hand, are mumbled, vague land acknowledgments at the start of meeting for business sufficient? Do the descendants of those who were so harmed even want to hear my moanings about the guilt of my ancestors, or would they turn to me and ask, “So what are you going to DO about it? Have I sought them out? Have I listened to their voices and heard their needs to bring healing? Have we, as the broader Fellowship of Friends?

I do not believe I can renounce my ancestors, nor would I wish to. What I can say is this: I am sorry. From my heart, I am sorry.

I am sorry for the harm done to Zitkála-Šá and her friends. How I wish I could go back in time and be the one to protect them, to comfort them when they had no comforter, to listen to them in their own authentic voices. I am sorry for the loss of so many beautiful cultural identities. I am sorry, but is sorry enough? It may be a start, but I fear that wishing for an impossible past is but weak solace to those who stand as inheritors of those long-ago traumas today.

Ironically, I think I can also turn to my ancestors for models of what genuine, heartfelt redress really looks like. Both lines of my mother’s grandparents were descended from southern Quaker families who were enslavers. Following the calls of their faith in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth centuries, my great-grandparents emancipated the enslaved people.

I thought when I heard these stories that they were mere hollow self-congratulation — “Look at us—we stopped doing evil of our own accord without even being forced to it.” I now think that I missed the point. The point was not self-congratulation, but rather a recognition of inherited obligation. The same family that, according to family tradition, had been the last to emancipate was also the family that subsequently became most active in the Underground Railroad. After the Civil War, my newlywed great grandparents—one the son of the aforementioned trustee at White’s Institute – rushed off to teach at another Quaker institute, Southland Institute, formed to offer an education to the newly freed men and women of the Arkansas Delta region. Thirty years later, when the Institute was hit by a tornado and then torched to the ground by an arsonist, they returned again, this time as its leaders, to supervise its rebuilding and assure the continuance of its mission. Is that legacy of service to the descendants of the despoiled what true redress looks like?

What their example says to me is that “Sorry” may be a beginning, but it is not enough. The deeper question posed by historical obligation is not what we owe the past, but how will we repay that debt in the present for the sake of the future?

References

Green, Alice P., History of White’s Manual Labor Institute, Scott Print., 1929, 22 p.

Minutes, Indiana Yearly Meeting of Friends, 1870, p. 52.

Zitkala-sa (Bonnin, Gertrude), American Indian Stories, 1921, republished in e-book format, 2003, Project Gutenberg.

Allen McGrew is a member of the QEW Steering Committee, worships with Dayton Friends, and is a professor at the University of Dayton in Ohio.