When Climate Change Gets Personal

By Gayle Matson

FOR 60 OF MY 65 YEARS I lived in Seattle and Portland, surrounded by snow-capped mountains and lush forests. The natural beauty of the Pacific Northwest is truly spectacular, though climate change has brought even rainier winters to the area. Last year, after pining for sunnier weather and a less congested city, I relocated to the pretty college town of Chico, California.

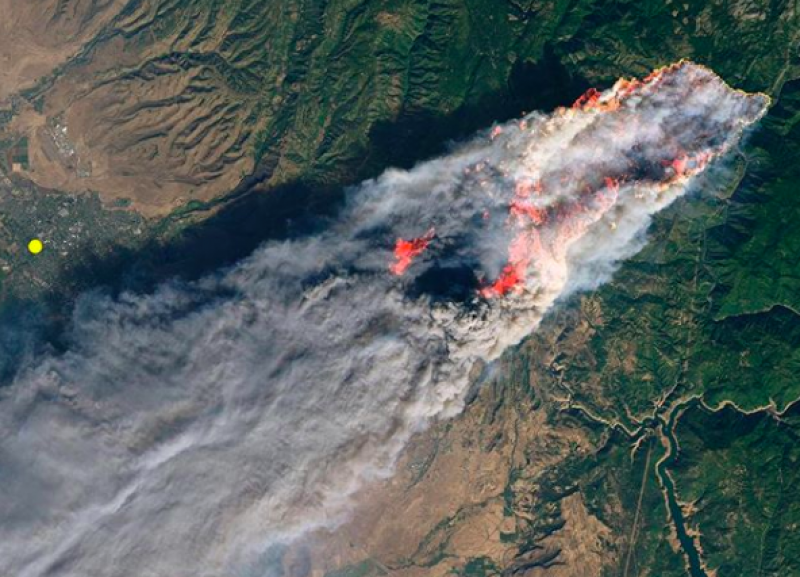

I definitely got my wish for less rain. In July, August, September, and October it did not rain one single day in Chico. By the morning of November 8th it still had not rained. As I sat outside that balmy morning with Quaker friends visiting from London, one of them looked up at the dark clouds gathering on the horizon and said, “We’re getting some rain!” Then we saw the sun peeking out, low and weirdly blood-red, and I said, “Oh no, it’s fire.” I called out to one of my new neighbors as he walked his dog, and pointed at the sky with a quizzical look. “There’s a little fire up by Paradise,” he called back. “How far away is that?” I asked. “Maybe 12 miles as the crow flies,” he answered.

By noon it was dark as night and cars were bumper-to-bumper, streaming out of town. Air quality wasn’t affected right away—the smoke rose straight up over town and traveled west to the Bay Area. My neighbors were going about their business; no one seemed panicked. “Should we be worried?” I asked my neighbor. “I have a go-bag packed, myself,” she said. “I can’t really see how the fire would reach us here,” I said hopefully. “That’s because you don’t know the area,” she replied.

By evening, survivor stories and apocalyptic video of the hellacious escape down the hill through the firestorm began appearing on the local news. Chaos had descended upon Chico. Evacuees were desperate to know the fate of their homes, pets, neighbors, and loved ones. None of us knew then that 86 deaths had occurred and 19,000 structures had been burned, most in the first five or six hours of the fire. Some 52,000 people were under evacuation order from their homes and workplaces. Shelters were overflowing, the fairgrounds were full, the Walmart parking lot became a tent city. Chico residents scrambled to make room in their homes for displaced friends, relatives and co-workers. My neighbor took her son’s family of four, their two big dogs, and her daughter-in-law’s mother into her two-bedroom home.

It took more than two weeks to contain the Camp Fire. The total property damage was estimated at $16.5 billion, a quarter of which was uninsured. More than 240 square miles were burned. Three Chico Friends Meeting families lost their homes. Two relocated in Chico, and the other moved closer to family in another state. Many Chico Friends took in evacuees, and some continue to house fire victims. Chico Friends Meeting received contributions from meetings and individuals around the US and abroad and established a fund to help those most affected by the fire with the least access to other means of support and assistance. The wider Chico community stepped up to the challenge of disaster relief and continues to stretch to accommodate the needs of fire victims. The town’s population expanded by 20 percent overnight, stressing infrastructure such as roads, schools, water and even sewage.

I first awoke to climate change as a moral issue when I heard Bill McKibben speak some 15 or more years ago. Since then, like many Friends I have taken what steps I can to reduce my carbon footprint—changing my travel habits, altering my diet, driving an electric car, installing solar panels on my Chico home. But on November 8th, 2018, climate change got very, very personal for me, and now I am called to do more. I’m not sure yet exactly what that activism will look like, but I am clear that I’ve got to take it up a notch and work more proactively for climate justice.